Little blue plaques

More than 150 years ago on Holles Street in London a little blue plaque was erected to mark the spot where Lord Byron was born. Now there are an estimated 45,000 of these markers across Britain but, as Shaun Soanes explores, could the writing be on the wall for these commemorations?

The built environment provides the setting and backdrop by which we live our lives. It impacts on our senses, our emotions, our sense of community and general wellbeing. It also links us to our present, our future and our past.

This explains our attachment to the renowned blue plaques scheme which began in London and has played an important role in the history of the conservation movement.

But former Radio 1 DJ Mike Read, who is chairman of the British Plaque Trust, believes we might be getting a bit carried away with all these commemorations.

What makes a building special?

Mike has a point.

While English Heritage, which runs the official blue plaque programme, claim just 10 bonafide blue plaques are put up a year, there are no restrictions on installing less official plaques.

One plaque in Oldham locates the site of “the first British fried chip” and one on a building in Dover commemorates where David Copperfield, a fictional character invented by Charles Dickens, “rested on the doorstep”.

There is even a young artist – Danny Coope – who will research the former residents of any address in the UK, creating a blue plaque for the venue for just £50.

Well, that’s Christmas covered!

It would be easy to feel dismayed by this “plague of plaques” – as some have declared it but I think these concerns are missing the point.

It shouldn’t really matter whether the person commemorated was a great statesman, a fictional character, a local legend or a national treasure. The more plaques the better.

In fact, I think we need a bit more diversity. And I’m not the only one.

Female figureheads

In the year that marks the centenary of women’s suffrage, English Heritage hoping to raise awareness of women who have made an impact on history, by redressing the lack of women celebrated on blue plaques.

Despite women’s inarguable contribution to British culture, out of the 903 plaques placed on buildings across the capital, a measly 111 commemorate women – that’s just 14 per cent. Out of all the blue plaques, just 4 per cent of roundels honour people of colour.

In a drive towards achieving parity, the organisation is calling upon the British public to nominate the women from history they believe are worthy of blue plaques

Current plaques dedicated to women include the computing pioneer Ada Lovelace, the DNA scientist Rosalind Franklin and the first woman to sit in parliament, Nancy Astor.

More recent recipients include the cookery writer Elizabeth David and Agnes Arber, a botanist who published more than 90 scientific papers and eight books

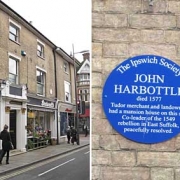

Homegrown plaque holders

Royalty, authors, pop stars, suffragettes and mayors are remembered by blue plaques across the East.

They include Margery Allingham, who is known as one of the queens of crime-writing and wrote a book about her home village Tolleshunt d’Arcy during the Second World War, and Constance Andrews, who was one of four women honoured with blue plaques in Ipswich.

The plaque was installed on Arlingtons Brasserie in Museum Street, where Constance led the 1911 Votes for Women protest against the census.

Most memorials to the world-famous group may be in their home city of Liverpool, but there is also a blue plaque to The Beatles in Norwich. This is one of a series of plaques put up by the EDP and Norwich School of Art and Design highlighting surprising aspects of our region’s cultural history. It is attached to Grosvenor House, Prince of Wales Road, in memory of their only concert in the city, at the Grosvenor Rooms.

Composer Lord Britten’s (1913-1976) name is closely associated with Aldeburgh, where he founded the famous annual festival and a blue plaque has been placed on the Crabbe Street site of Crag House in the town, where he lived and worked. This plaque was unveiled in 1978, two years after his death.

A plaque in memory of legendary DJ John Peel (1939-2004) was unveiled by his wife, Sheila Ravenscroft, in his home village of Great Finborough in Suffolk last year.

A place in history

In my opinion blue plaques are the most beautifully simple way of evoking the layered history of a location, and they greatly improve our experience of a city, expanding the imagination and animating the street.

Reading a plaque, you become linked not just to the past, but to your physical surroundings.

This is part and parcel of what architects strive to do – connecting people to their environment.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!